Declaring Myself for the 2013 MLB Draft*

In June, Major League Baseball will hold its annual “First Player Draft.” I’m ineligible, because I could have been drafted in 2000 but wasn’t, and therefore, am effectively a free agent, able to sign with any team which wants me. But let’s put that aside and, for sake of discussion, assume that I’m just as draft-eligible as anyone else.

If any MLB team wants to draft me, great! Here are my demands:

1. I want a $50,000 signing bonus.

2. I will retire the next day.

3. I will only sign with the Mets.

This is a great deal for the Mets and I hope they take it. Seriously. 1

Why?

Starting last year, MLB instituted this weird slotting/cap/tax system. Before last year’s draft, BaseballAmerica explained it well:

[Every pick in the first ten rounds is assigned a dollar amount.] A team’s total budget for the first 10 rounds is the sum of the numbers for all of its picks, so teams that have extra picks and early picks have more money to spend. The Twins have the highest budget this year, with the second overall pick as well as extra picks.

Teams can spread the money among their picks in the top 10 rounds in different ways so long as they stay under the total budget. For example, the Astros could sign their No. 1 pick [assigned a value of $7.2 million] for $5.2 million and spread the extra $2 million among other players. However, if a team fails to sign a player, it cannot apply the budgeted amount for that pick to other players and loses that amount from its overall budget.

See the loophole? If a draftee signs for less than the amount allocated, the team can use the overage on other players. But if a draftee fails to sign, that money goes away. (That happened to the Mets last year with the 75th overall pick when Teddy Stankiewicz didn’t sign.) This year, the Mets have the 76th pick (among many others), which should have an allocation of about $650,000 to $700,000. I propose that the Mets draft me, give me $50,000, and use the remaining $600k or so to sign actual players at amounts above their allocation.

This is, relatively speaking, a huge amount of money. The Mets have the 11th overall pick in 2013. In 2012, that pick was allocated $2.550 million. An extra $600k would bump that to over $3.1 million, which is around where picks 6 and 7 were. Being able to go over slot on a player there could allow the team to land someone who would otherwise be out of reach. Or, the team could use that money to effectively double the signing bonus for the guy they take at #84. There are lots of possibilities.

Unfortunately for me, I’m not draft eligible, though. But there are plenty of college seniors who are, and given the economy and their job prospects, this would be a pretty great thing for one of them.

Plus, I love a good loophole.

—

Update: Apparently, MLB already is on to this, and issued a memo threatening to void any picks which reek of this idea. Oh well.

Notes:

- Had I been draft eligible, I mean. ↩

Zach Braff, Amanda Palmer, and the New 90-9-1 Rule: The Indifferent, the Haters, and the Ones who Love You.

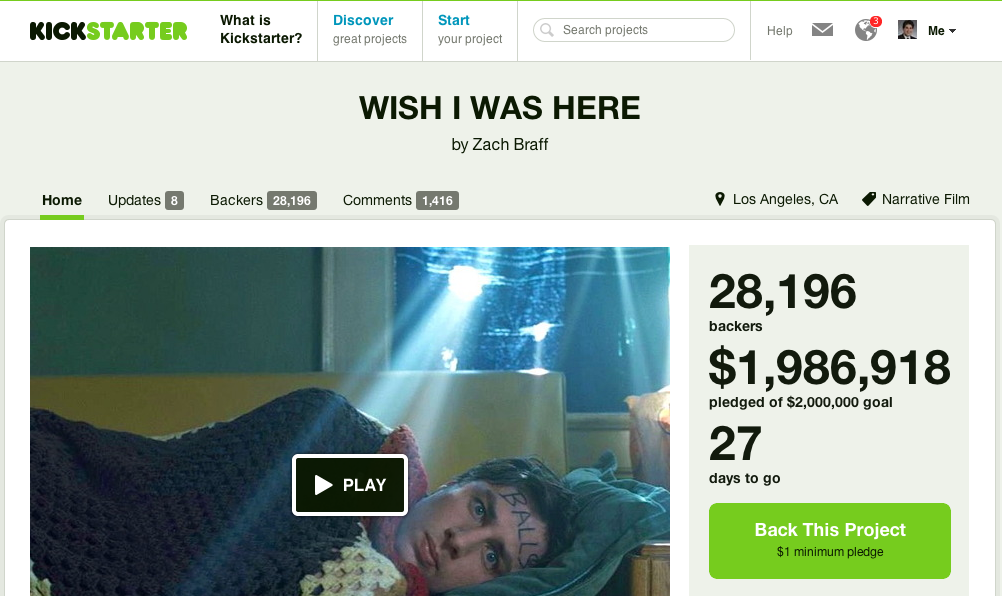

Zach Braff is going to raise over $2 million for a movie without a distributor, without a studio, and really, without anything more than a kind of strange pitch video.

For almost everyone, that’s a lot of money — a real lot, given that it’s hit that point in just a few days. But Zach Braff has money, of course; he starred in Scrubs and wrote, directed, and starred in Garden State, which made $35 million in the box office. He’s got money, and probably enough to make another movie. Regardless, he has access, name recognition, and all the other stuff that the “almost everyone” crowd lacks. Which is why there’s significant backlash against the project.

Amanda Palmer is in the same boat. Name recognition, access, and already a success, she’s a Kickstarter wunderkind now being mocked.

Good. Because they don’t need everyone to like them to be successful.

* * *

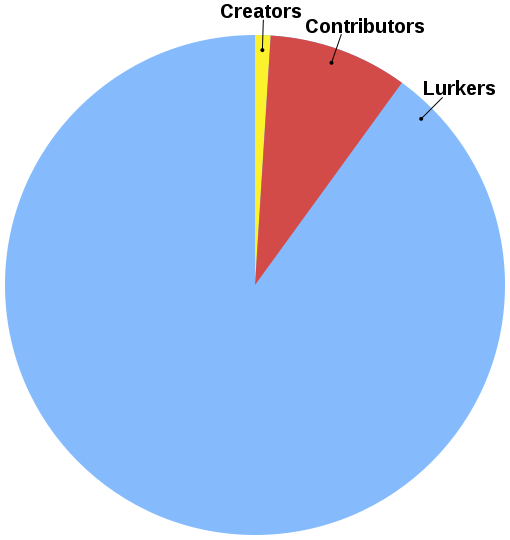

There’s an informal rule of online communities called the 90-9-1 principle. 1% of the user base creates the vast majority of the content; 9% dabbles; 90% participate only in minor amounts if at all. The point is that you don’t need a whole lot of people to participate in order to create something pretty impressive. 1 That’s how Wikipedia became the behemoth it is today.

The funding of content can — and, I think will — follow the same pattern. Once a person has a large enough following 2, you can fund basically anything you’d like. Braff has only 28,000 backers of the above-cited Kickstarter, which is much less than the 1% of the weekly viewership of Scrubs, for example. The traditional 90-9-1 principle applies here, as a very small amount of backers are (via their dollars) creating something for the 90.

But what about the haters? That requires another 90-9-1 rule.

* * *

I’m going to go out on a very tiny limb here: Braff is going to get to make his movie, and pocket a significant (to a normal person) amount of money for himself. Similarly, Amanda Palmer can raise six or seven figures for a new album whenever she wants. But more importantly, they can sell the risk to their fans. Compare what they’re doing/did to Louis CK’s $5 download or Andrew Sullivan’s decision to go indy. Braff and Palmer didn’t make the content and then sell it. They didn’t quit their jobs and go on their own. They make their art conditional on it finding dollars, not the other way around.

People who don’t particularly like Louis CK or Andrew Sullivan haven’t taken up arms against their declarations of independence with anywhere near the fervor that we’ve seen for Braff and Palmer. 3 It makes a lot of sense that there’s backlash against the latter because of two simple facts:

1. They’re rich, an better able to shoulder that risk than the rest of us, who typically aren’t rich.

2. They don’t need to sell that risk in order to make what they want to make.

Point one there requires very little explanation, if any. The second one, though, probably does. The operative word is “make.” They could have made their film or album — the question is, could they sell it? If Braff wanted to make his “Wish I Was Here” movie 4, he could have. That’s true even if he wanted to make it without anyone else having final approval over what went into the movie and what got cut. He could have self-financed, found out-of-industry investors, or taken on debt. Most of us don’t have the wealth, reputation, or connections to do that, but he clearly does; that’s how he created Garden State. I don’t really know what happened with Amanda Palmer, but I’d be surprised if she didn’t have a way to fund the creation of the album she wished.

Traditionally, artists don’t take this risk. The publisher or label or studio does; the artist by and large gets paid either way. Louis CK and Andrew Sullivan are breaking the mold pretty dramatically here when you look at it from that vantage point. On the flipside, it kind of makes sense that Braff and Palmer don’t want to be in that seat. Generations of artists simply haven’t.

On top of that, the upside from going indy is big. They don’t have to pay for a ton of overhead relative to traditional methods, the costs are much lower. There are many fewer stakeholders in the project, they receive a higher percentage of the payout. But we already knew that.

Combine that, though, with the ability to sell your risk to your fans, and we’re onto something big. (That’s really Kickstarter’s whole thesis.) If you have a few million fans and 1% of them pony up $100 on average, you’re golden.

But again, what about the haters?

The vast majority of people in the U.S. have no idea who Amanda Palmer is. More know who Zack Braff is, but there are 300-something million of us at, at its peak, Scrubs only (“only!”) had 15 million viewers. That’s your first 90% — the group of the addressable market (TV owners? movie goers?) who are indifferent to or unaware of the artist. They just don’t matter, at least not insofar as funding the content is concerned. 5 Your fans are the 1%. A small fraction of them (1% of the 1%) will fund the creation of the content, and the rest of them will likely buy it once it’s made, unless it sucks. 6 And then there’s the haters. As long as they’re a relatively small group — even if they’re much, much larger than your true fans — you’re probably OK. That’s the 9%. Like the original 90-9-1 principle, the actual percentages are made up; they’re demonstrative of the underlying theory.

In the end, the fans matter and the antagonists — unless there is an absolutely enormous amount of them — simply don’t.

———

Notes:

- The 1% isn’t intended to be accurate; rather, it’s demonstrative. In the case of Wikipedia, it is certainly overstated. If you look at the growth of Wikipedia (see the graph here) you’ll note that it crossed 1 million articles in early 2006. About 70% of the US population was online by then — that’s about 200 ml\illion Americans.. But there were only about 50,000 active editors on Wikipedia in 2006. If that’s 1% of the Wikipedia readership, then only 5 million of that 200 million (2.5%)- nowhere near the reality at the time. ↩

- I realize this is a big given. Few people have the following of a Zach Braff or Amanda Palmer, and in both those cases, they developed their audiences only after a major entertainment brand or two “discovered” them and made them famous. A large part of the backlash against them is due to this. I see this as a temporary problem ripe for disruption and *not* a true barrier to entry for the heretofore undiscovered creators. But that’s a story for another day. ↩

- A large part of the anti-Palmer backlash is because she tells her story as an outsider — as if anyone could do what she’s done — which doesn’t jive with the fact that she was part of the duo the Dresden Dolls, which released two studio albums under a Warner Music Group subsidiary’s label. But even if she acknowledge that fact, I think there’s still be meaningful backlash because she’s not assuming the risk of her work not selling. ↩

- It bothers me to no end that he said “Was” and not “Were.” ↩

- Much like Wikipedia, though, they could become customers/users later on. There’s a lot of upside here, although it’s hard to get it. But imagine if Braff’s movie gets a Best Picture nomination… ↩

- There’s a HUGE amount of upside here. That’s why Garden State grossed $35 million at the box office. Or, put another way: if 350,000 people see this movie in theaters, at $10 a ticket, that’s $3.5 million — 10% of what Garden State made. If Braff gets $2 per ticket, that’s $700,000 right to him. Wow! ↩

Allen Stern, Who Dedicated His Life to the Health of Others

My friend Allen Stern passed away earlier this week, unexpectedly. Many people I know also knew him, and I could not be more saddened to be sharing this news.

I don’t have any details — his sister Sari posted an announcement about an hour ago on his Facebook page — except that this all came as a shock to all of us who have spoken with him recently. I’ve kept in touch with Allen primarily via IM since his move to Austin about two or so years ago, and he had incredibly reinvented his life. Less than a month ago, he posted a pair of pictures of himself, one from December 2011 and another from March 2013 — he had lost 125+ pounds.

Allen’s transformation was bigger than that, though. Last year, he sold CenterNetworks and now, was working on selling his startup CloudContacts. He was re-dedicating his life to help people learn to live a healthy life, and had focused his energies on LetsTalkFitness. He was reaching thousand and thousands of people each week via the site, Facebook, Pinterest, Instagram, and had 3,000 people signed up for his Smoothie a Day email newsletter. (It was a growing success story; he was at 93 people on September 30th!) He took incredible pride in this, crafting images that would make a professional photographer nod in agreement, all to spread the message of the value and importance of good health. He was having an impact, too; he regularly shared with me the wonderful comments people emailed him and left him on Facebook, thanking him for inspiring them.

I last spoke to him (via IM) on April 1st. He was working on a green smoothie e-book and looking at ways to monetize LetsTalkFitness better — he truly wanted to make this, his life’s calling, his trademark business. The last thing of substance that he said to me best summarizes his dedication. He had found an ad network which could monetize his image views, but he didn’t want to use it. He was concerned that, if he posted an image of a smoothie, and someone got an ad for “some garbage food” on it, that would be bad — he only wanted to promote healthful options.

I don’t know what’s going on regarding funeral arraignments nor how to best pass one’s condolences on to his sister. My best guess is to post a comment on her Facebook post.

RIP, Allen. You’ve made the world a better place, and you will most certainly be missed.

Originally published on April 6, 2013Hug Your Fans and They’re Fans For Life

I tweeted that out today while watching the below. It resonated.

When I sent the tweet, I didn’t realize that Billy Joel actually hugged the audience member — that didn’t happen until the end. I wasn’t talking about a literal hug, but the figurative idea of embracing your audiences in an incredibly meaningful way.

While watching the video, think about how many people will, forever, think of Billy Joel in a much better light. Obviously Michael Pollack, the freshman pianist, will remember this forever. But so will his friends who helped get Joel’s attention when Pollack wanted to ask the question. So will the people who were sitting in the audience who didn’t know Pollack. And so will many of us who watched the video and shared it.

That’s the hug.

Originally published on March 12, 2013Writing for Exposure: What Publishers Should Promise When They Aren’t Paying

It’s been almost a week and Twitter is still abuzz over the issue of publishers not paying writers, but instead promising “exposure” to their audience. (If you haven’t been following, google “Nate Thayer The Atlantic” — I won’t waste anyone’s time recapping it here.)

I’ve written for exposure a lot over the last two years. I write for free to gain exposure for Now I Know, and more specifically, for subscribers. Most of that “writing” is just me letting other places republish my work, but sometimes there’s a bit of editing involved, reworking, or combining of things.

My goal is to gain subscribers for my Now I Know email newsletter. I’ve come up with a series of requests I make of the publisher, which began with the awesome people at mental_floss, who understood that goal when I first wrote for them and helped me come up with ways to maximize that. What do I ask for? (a) A series of clear, call-to-action language, explaining why the publisher’s readers should subscribe to Now I Know; and (b) a promise/explanation of how the publisher focus their audience on my article.

Most of the places I’ve written for have done both of those, but in two cases — Business Insider and Huffington Post — they haven’t, really. I knew that going in and I do not want to cast aspersions here. Both were entirely professional and forthcoming about how they intended to promote my piece (i.e. give me exposure beyond the resume line) and even though it didn’t meet my normal requests, I chose to experiment. Both experiments went as well as you’d expect, which is to say not well at all.

GOOD vs. Business Insider

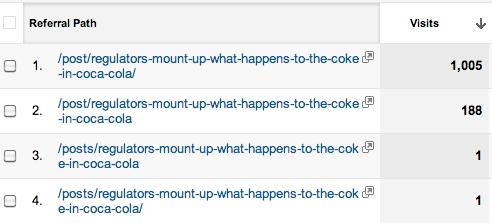

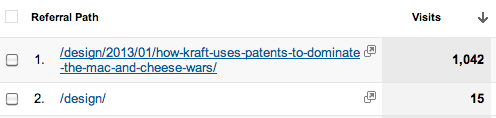

About a year ago, GOOD republished five articles of mine. That relationship was the product of a healthy back and forth between me and an editor there, describing how they’d promote the article and how the links to Now I Know would look. The first article, here, has sent over about 1,200 visitors since, as evidenced below.

After that article ran, Business Insider approached me and asked if me for permission to republish the same article. I tried to get them to engage on the same questions I asked of GOOD, but it wasn’t happening. I figured I’d say yes as a test. They have a much larger audience than GOOD, and if they could drive traffic, great. But I realized that was very unlikely, as their audience is fragmented across their site and unless I received prominent placement, it wouldn’t be worth it for me.

A year later, the results proved that BI wasn’t worth my time at all:

That’s 115 visits. About 100 of them are from this article, which is the same as the GOOD one (and incorrectly states that the article originally appeared at GOOD).

Smithsonian Magazine v. Huffington Post

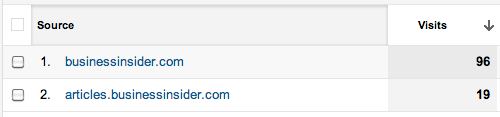

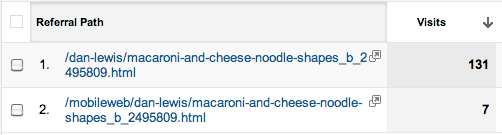

In January, Smithsonian Magazine republished an article of mine about Kraft’s use of patents to protect their mac and cheese shapes. This wasn’t the first piece I’ve had there, but it did well, sending 1,000 or so readers to my landing page:

The Smithsonian relationship developed the same way as the mental_floss and GOOD one, and works similarly.

A day or so later a HuffPo editor approached me about republishing that article. HuffPo and BI’s business models are similar, and I approached the conversation with the HuffPo editor like I did the BI one. In the end, the article ran, again as an experiment in my eyes.

The results:

Not terrible, honestly, but not really great. And not really worth the work to get another one in the system, especially because I don’t have much if anything of a relationship with an editor there, so I don’t know if my next piece will get anywhere near that much (“much”) exposure.

“Exposure” is an amorphous, oddly-defined or undefined term. It probably makes very little sense for a full-time freelancer to give the Atlantic a 1,200 word cutdown of a longer piece for free, as a one-time exposure to a subset of their audience is not very valuable to the writer. On the other hand, if the Atlantic were to offer a freelancer a week-long stint blogging for one of its more visible areas, that sounds good.

In my case? If HuffPo or BI were to come back to me and ask for another piece, I’d say yes — but I’d condition it on them providing the article the traffic I know they can provide if they choose to. If they ask why, I’ll send them here. And if they so no to that condition, they won’t get my permission. It can be worth it for me to write for them, but by default, isn’t.

Originally published on March 10, 2013Did NASCAR Admit to a Flagrant Violation the DMCA? I Say No

Background:

- NASCAR had a bad accident this weekend where a car exploded and stuff — tires, metal, etc. — went flying into the stands. People got hurt, some very badly.

- A fan took a video of the accident and posted it to YouTube.

- NASCAR used the DMCA to take down the video.

NASCAR explained what happened to the Washington Post, here. What they said is a bit contradictory, but here are the two parts I want to focus on.

One:

In an interview Tuesday afternoon, NASCAR Vice President of Digital Media Marc Jenkins made clear one point: “This was never a copyright issue for us,” he said. Nor was it a censorship issue. The matter related to the fans involved in the incident. “We blocked it out of respect for those injured,” says Jenkins.

And two:

As Jenkins explained, NASCAR owns the rights to video shot at the track but “we don’t enforce the guidelines unless the content is used commercially. … We do proactively go after pirated video of the television broadcast, but that’s the only time we use it.”

Dan Gillmor and I conversed on Twitter. He thinks that NASCAR, given the above (and the rest of the stuff I omitted — I don’t know exactly what sentences he’s relying on), “admits flagrantly violated the law” in taking down the video. I disagree. I don’t see an admission here. 1

Taking the second quote first, NASCAR believes it owns the rights to the fan’s video. They used their copyright of the video, as stated in the first quote, to require YouTube to remove the video. Their reasons for doing so — censorship, economic, because a Martian told them too, or to protect the privacy of potential victims — are irrelevant to their power to do so. The DMCA only requires that your takedown notice swear under penalty of perjury that you own the rights to the content; it doesn’t require you to explain why you want that particular piece of allegedly copyrighted content removed from the third party’s service.

While Jenkins also says (in the first quote) that “this was never a copyright issue for us,” I think he means to say that “this was never an economic issue for us.” In other words, NASCAR wasn’t trying to take down the video so they could sell their own crash footage. The other interpretation — one which suggests that NASCAR couldn’t lawfully remove the video — is entirely inconsistent with the second other quote. On the other hand, the rest of the first quote is consistent with the second. NASCAR believes they could have taken the video down for any reason or no reason at all.

If you credit NASCAR’s words here as honest — and I am doing that, but again, solely for the purposes of determining whether there’s an “admission” here — NASCAR didn’t violate any laws here. Rather, they’re claiming that they used their copyright to achieve a non-traditional goal.

Notes:

- To be clear, I think that the fan video was a fair use of NASCAR’s copyrighted content, assuming, that is, that NASCAR actually actually owns the copyright to the fan video in the first place. (And I think that’s unclear.) That’s another story. I’m focusing on whether NASCAR admitted to a violation here, not whether NASCAR actually overstepped its bounds. They probably did. ↩

Testing Polls. Vote If You Want To.

[socialpoll id=”4846″]

Originally published on February 15, 2013How I Found a Neat Story About an Island Nation Which Ran Out of Bird Poop

Today’s Now I Know is about a tiny island in the Pacific called Nauru. You should read it, here.

One of the questions I get most often about Now I Know is how I find all these stories. The answer is … long. I read a lot, people send me things, and I have a good eye for the obscure yet interesting things that I share (I hope), but that doesn’t really do the process — or lack thereof — justice. One story (this one) I learned about because it was summarized on the side of a truck I happened to see one day. 1 That’s an outlier, but you hopefully get the point.

Anyway, this Nauru one has a kind of but not really interesting back story. I follow Jeopoardy! champ Ken Jennings on Twitter. A few days ago, he tweeted out this:

The world’s only country without an official capital is sort of a bummer. cntraveler.com/daily-traveler…

— Ken Jennings (@KenJennings) February 5, 2013

I’m going to click that nearly 100% of the time, assuming I notice it (i.e. am looking at Twitter). I clicked, and the country is Nauru. 2 I skimmed the article (I even missed the part about the unemployment and obesity rates until now) but noticed the part about the bird guano. I went to Nauru’s Wikipedia entry, did some Googling for news articles, and came up with all the stuff you read about today.

You’ll note that I didn’t put in the fact that Nauru doesn’t have a capital. I left it out because it wasn’t really relevant to the story I was telling, and while it would have made for a decent bonus fact, the other one was better. At times, I’ll drop a “double bonus” into an email, and I considered it for this one, but I wanted to make sure I credited Ken Jennings for the tip, and figured this would be a good way to do it.

Notes:

- Literally, I walked into traffic to read it. Here’s a picture which someone else took of a similar truck. ↩

- There’s your bonus, bonus fact. Nauru has no official capital, and is the only country without one. That makes sense. It’s only 8 square miles, which is much less than Manhattan at 22 square miles. And Manhattan isn’t a country. It isn’t even a city! So how could it have a capital city? ↩

555 95472

555 95472 [dancing left, above], usually referred to as “5”, is a character in the comic strip Peanuts by Charles M. Schulz.

He debuted in 1963, and continued to appear on and off in the strip until 1981. “5” has spiky hair and sometimes wears a shirt with the number five on it. 95472 is the family’s “last name”, or more specifically their ZIP code. In reality, it is the ZIP code for Sebastopol, California, where Charles M. Schulz was living at the time the character was introduced. “5” has to keep telling his teacher that the accent is on the 4 in his surname. Snoopy is confused as to whether the boy’s name is spelled 5 or as the Roman numeral V.

As “5” once explained to Charlie Brown, his father, morose and hysterical over the preponderance of numbers in people’s lives, had changed all of his family’s names to numbers. Asked by Lucy if it was Mr. 95472’s way of protesting, “5” replied that this was actually his father’s way of “giving in.” “5” also has two sisters named “3” and “4”. (“Nice feminine names,” in Charlie Brown’s sarcastic assessment.) It can be assumed that their parents are named “1” and “2”.

Fantastic.

Originally published on February 3, 2013Teaching Square Roots to a Five Year Old

A week or so ago, we gave my five year old son a little solar powered pocket calculator to play with. He explored the key pad and it didn’t take long before he had a question we didn’t really know how to answer. He saw the square root symbol and wanted to know what it was.

We — adults, generally — understand them, at least in a cursory way. The square root of 4 is 2, or 9 is 3, of 16 is 4, etc. until probably 100 or 144. But we learned it a long time ago, and we probably can’t remember how we learned it. And almost certainly, we learned the concept well after preschool. So not only do we not know how to teach the concept generally, but we certainly aren’t good at teaching it to people who are much, much younger than typically learn it.

But five year olds can be persistent so I gave it a go. I don’t know how much he understands the concept, but my son definitely gets some of it.

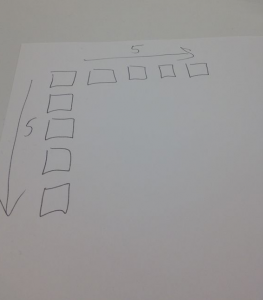

I started off by drawing a row of five “blocks,” careful not to call them squares. Then we counted them together. (Being very deliberate in each step seemed to help a lot.)

After that, I drew a row of five more blocks (well, four more, double-counting the corner) across.

And then, we counted and labeled the sides.

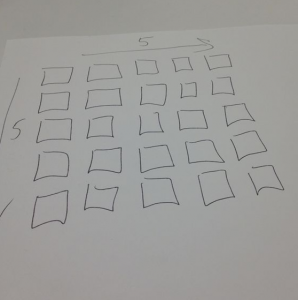

I then took a bit of a leap, and explained that these two sets of five blocks were the “roots” of a square, kind of like how a tree has roots. And a really big square can grow from the “roots.” We just needed to fill in the rest of the square with more boxes. So we did.

We then counted the boxes and, of course, ended up with 25. Our 25-box square had a root of 5. And to demonstrate we were right, I asked him to put the number 25 into his calculator and hit the square root button. When the five popped up, he screamed “WE’RE RIGHT! IT’S FIVE!”

I repeated this whole thing for 4, 3, 2, and then 1. And then I asked him to explain it back. He was so excited he ended up telling his preschool teachers about what he “learned”… and hopefully, understood.

Originally published on January 31, 2013