A Radio Strategy in a Digital World

Last fall, I met with a friend who had recently spoken with an executive at another (not the Mets) professional sports team in New York. The exec said that the single biggest change in the sports world in recent history was the advent of sports talk radio; specifically for you New York sports fans, WFAN. Before WFAN, teams had a cozy relationship with beat writers and newspaper columnists — that is, the media — and the reporters and columnists would, by and large, echo the company line as gospel. The team controlled information and access; in exchange, they left to the media the “right” to distribute the story. It was a win-win, as the team got positive press and the journalists were glistened the experts. For any baseball fan, this is self-proving: the Baseball Writers Association of America decides on the end-of-season award winners and Hall of Fame inductees. (In any other industry do journalists decide award winners? Could you imagine if the editorial page of the Washington Post named the Nobel Peace Prize winners?)

Sports talk radio changed all that, for at least three reasons:

- All of a sudden, there was a lot of space for analysis, even if the analysis was mostly blather. When a radio host has to fill four hours a day, five days a week, he has to say more than the snippet the team gives him.

- The snippet gets challenged — especially by fans. Radio gave the fans a chance to sound off, via call-in shows. While not the focus of talk radio, there was no equivalent in sports. Most newspapers and magazines published letters to the editor, but not about sports minutiae, e.g. whether a specific player should be sent to the minors.

- Reporters and columnists became sources. Literally. Radio hosts would invite them to call in; the hosts would put the questions to the writers. Writers reply, and are challenged by the host (e.g. “Why did the coach call that play at that moment?”).

The end result: Beat writers no longer had a monopoly on the sound bite, and when that went away, so did the teams’ cozy relationship with those beat writers (and the rest of the media population, for that matter).

The media wanted more access, as individuals wanted scoops; the team wanted more control, as stories took on live of their own. The two goals don’t mesh. That’s why we have an era where it’s not uncommon to see players yelling at reporters (or pushing away cameras); why Theo Epstein once donned a monkey suit to avoid reporters; why Allen Iverson talks about practice.

But today, the landscape has again changed. With Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter, ideas move way too rapidly to play the cat-and-mouse game between teams and the media. And even more importantly, the new landscape is participatory, not broadcast. There is no need for the team to play this cat-and-mouse game because they can — and should — manage their own memes.

Unfortunately, the radio era harmed the notion that “conversation” and “participation” are laudable goals, for in the radio era, attempts at either were doomed to backfire. So, I suspect, it will be a long time before those once burned get over their new media shyness.

Step by Step aired for six years on ABC’s “TGIF” lineup, and then for a seventh on CBS, totalling 160 episodes. At thirty minutes per episode (including commercials — this was pre-DVR), a person who watched the entire run wasted over three whole days of his or her life. It is still being aired in syndication on ABC Family: once a day on weekdays and twice-daily on weekends.

Step by Step aired for six years on ABC’s “TGIF” lineup, and then for a seventh on CBS, totalling 160 episodes. At thirty minutes per episode (including commercials — this was pre-DVR), a person who watched the entire run wasted over three whole days of his or her life. It is still being aired in syndication on ABC Family: once a day on weekdays and twice-daily on weekends.

We both got on the first car of the train. Before the train reached the next station less than two minutes later, the guy was in the middle of the car, panhandling. Nothing too strange, except he wasn’t in his wheelchair. He was scooting along, pushing himself forward with his arms while simultaneously carrying a coffee can of change and small bills. He said nothing — the jingle of the change and the spectacle of a legless man moving slowly though the subway car spoke volumes for him. And when the train stopped at the next station, he didn’t. He moved on, reaching the end of our car just after the train disembarked. Then he went through the doors at the end of the car and into the next one — leaving his wheelchair behind. I waited a stop or two and, amazed, took the picture to the right.

We both got on the first car of the train. Before the train reached the next station less than two minutes later, the guy was in the middle of the car, panhandling. Nothing too strange, except he wasn’t in his wheelchair. He was scooting along, pushing himself forward with his arms while simultaneously carrying a coffee can of change and small bills. He said nothing — the jingle of the change and the spectacle of a legless man moving slowly though the subway car spoke volumes for him. And when the train stopped at the next station, he didn’t. He moved on, reaching the end of our car just after the train disembarked. Then he went through the doors at the end of the car and into the next one — leaving his wheelchair behind. I waited a stop or two and, amazed, took the picture to the right. Dutifully, I went down there to get some Children’s Tylenol — or, rather, the generic equivalent. I spoke with the manager, who informed me that the name-brand product had been recalled, so they didn’t have it, and that Duane Reade does not carry a generic.

Dutifully, I went down there to get some Children’s Tylenol — or, rather, the generic equivalent. I spoke with the manager, who informed me that the name-brand product had been recalled, so they didn’t have it, and that Duane Reade does not carry a generic. Today, it’s

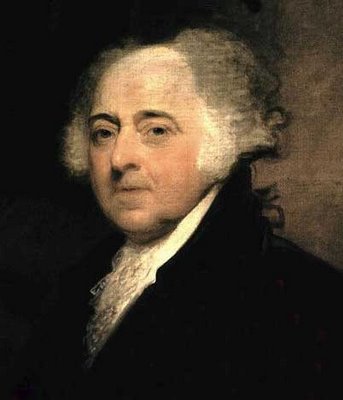

Today, it’s  That same day, former president John Adams came up in a conversation with a friend. We were talking about Liz Cheney’s objection to American lawyers representing Al Qaeda members, and Adams — who represented British soldiers (successfully!) charged with crimes stemming from the Boston Massacre — naturally came up. We both knew who he was, basically — the second President of the United States, a Boston patriot, even cousin of Sam Adams. But beyond that? Nothing. Not even enough to fill a top 10 list.

That same day, former president John Adams came up in a conversation with a friend. We were talking about Liz Cheney’s objection to American lawyers representing Al Qaeda members, and Adams — who represented British soldiers (successfully!) charged with crimes stemming from the Boston Massacre — naturally came up. We both knew who he was, basically — the second President of the United States, a Boston patriot, even cousin of Sam Adams. But beyond that? Nothing. Not even enough to fill a top 10 list.