Imagine you owned a Major League Baseball team; well call it the Mets. Your star player (“David Wright”) is, inexplicably, striking out a lot, and your team is having a bad year. What message do you expect the sports media to hook into and spread?

In the Mets’ case, the media has hooked onto a meme. “David Wright is striking out a ton, and it’s hurting the team.”

But it’s not true. Yes, he’s striking out a lot — but he’s also outperforming the rest of his team. He’s second on the team in home runs, leading in runs batted in, gets on base more often than anyone else, and even is second (by one) in stolen bases. He is on pace for a “30/30” season — thirty homers, thirty stolen bases — and 100+ runs batted in. Yes, he’s striking out a lot more than in years past, but he’s having a good, if not great year. He’s an asset, not a liability.

The Mets should combat this, just like any organization should if an asset is being treated like a liability by the press. While the example above is sports related, the solution can apply to anyone in the public sphere.

The Three Ds of Meme Management

1) Develop your own soundbite.

The term “soundbite” may come off as negative, but it’s descriptive here. You need to find a message and boil it down into a sentence or two. I did that above.

The message has to be short and to the point. The more you say, the more things there are for the chattering class to analyze, refute, and often (and unintentionally) distort. Be clear and succinct.* Stay on message. You want to tee up your idea and hope that it spreads, winning the day; or at least, is something you can keep reiterating across various media channels.

* And, it should go without saying: Choose your words carefully to make sure you don’t sound stupid. Last night, when the Mets removed their starting pitcher from the game after five pitches, the pitcher claimed that he was not injured and was appalled by the decision to remove him. The pitching coach’s response: that the pitcher is a “habitual liar” when it comes to his playing condition. Big mistake.

2) Distribute the message yourself.

You cannot control your message, no matter how hard you try. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try.

But the definition of “trying” has changed from the press conferences, interviews, and press releases rubric of years past. It’s not enough to sit around, crafting the message and choosing which media outlets you’ll speak with. Nearly any organization can distribute the message themselves. Have key stakeholders (the general manager? the owner? even a PR representative or spokesperson) start a blog. Create an organizational Facebook page. Use Twitter accounts, etc. None of this is groundbreaking advice, so it is rather absurd that organizations have not yet caught on. Again, take the Mets for example. To the extent they use any of these tools — and it is minimal — it’s for marketing purposes only.

3) Defend your message.

Once others hear, repeat, rehash, and discuss your take on the goings-on, some will criticize it. You need to be ready to defend it.

That means engaging the critics on their turf, as the Mets and other sports teams often (and sometimes poorly) do take the media to task, head on. But rarely do you see a team do this. Instead, they hold press conferences, go on radio shows, issue statements, etc. They don’t ever engage the fan directly via media properties they control.

Perhaps the most valuable aspect of Twitter, Facebook pages, and blogs is that you can receive — and reply to — feedback right then and there. And the replies are public, so even if you don’t convince the skeptic, you may convince someone else listening or watching the argument. Overlooking this value, in the current “social media” climate, is fatal.

* * *

Applying the three Ds is not difficult. It simply requires time and consistent effort.

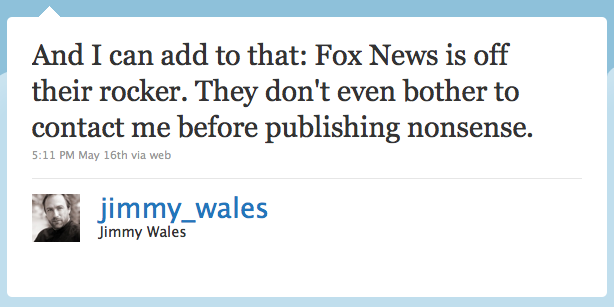

One such example occurred last week, when Fox News ran an article claiming that Wikipedia founder (and my former boss), Jimmy Wales, was stripped of editorial rights due to an unrelated scandal. He took to Twitter (and to TechCrunch, a third party blog) to set the record straight and defend himself:

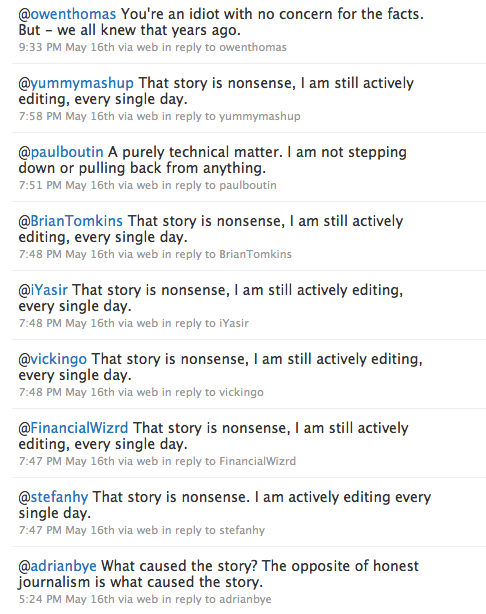

The defense consisted of pointed replies to those who reacted skeptically:

Effective? You bet. The passion plus the time investment means that he’s taking it seriously; that this is important; and that the current media-driven meme is incorrect. It’s believable and simulteaneouly remarkable.

It’s the approach everyone should be taking in managing the media sentiment of their organization. Don’t follow the sports teams’ model.