The Wikipedia Reading Club: Jackie Robinson

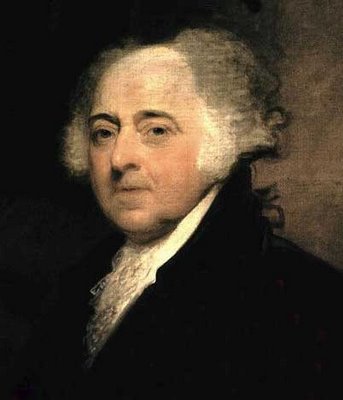

Yesterday, I kicked off the Wikipedia Reading Club with this post on John Adams’ entry. Click that link to learn more about the Club and how to participate; read on if you already know.

Today, it’s Jackie Robinson. As a die-hard baseball fan, I know more about Robinson than the average person, I’d bet — I know he broke the MLB color barrier, of course, but I also knew a good amount about the details of his playing career; even the fact that he retired rather than accept a trade to the San Francisco Giants (although I did not realize that he had decided to retire prior to the trade). Here are a few things I learned; please share your thoughts in the comments, as always.

Today, it’s Jackie Robinson. As a die-hard baseball fan, I know more about Robinson than the average person, I’d bet — I know he broke the MLB color barrier, of course, but I also knew a good amount about the details of his playing career; even the fact that he retired rather than accept a trade to the San Francisco Giants (although I did not realize that he had decided to retire prior to the trade). Here are a few things I learned; please share your thoughts in the comments, as always.

In junior college, Robinson had a run-in with the police over what he saw as a racially motivated detainment of a friend. Specifically, “[a]n incident at [Pasadena Junior College] illustrated Robinson’s impatience with authority figures he perceived as racist – a character trait that would resurface repeatedly in his life. On January 25, 1938, he was arrested after vocally disputing the detention of a black friend by police. Robinson received a two-year suspended sentence, but the incident – along with other rumored run-ins between Robinson and police – gave Robinson a reputation for combativeness in the face of racial antagonism.”

This jumped off the page for two reasons. First, I thought one of the reasons Robinson — beyond his supreme talent for baseball — made for a great candidate to break the color barrier is because he was one to turn the other cheek; it turns out, I was entirely wrong on that point. Rather, Branch Rickey and Robinson had to come to an informal agreement that Robinson would turn the other cheek in spite of his history of doing the opposite; I see this as a major testament to Robinson’s will and fortitude against hate that I can’t even imagine.

Second, six years after he debuted, the Yankees were still an all-white ball club. They had a guy named Vic Power in the minors was was destined to get a call to the bigs. But the Yankees, allegedly fearing Power’s temperament, kept Power in the minors for the 1953 season — they did not even extend him a Spring Training invite. Again, allegedly, the organization did not want Power to be the first African-American Yankee, instead preferring Elston Howard to take that honor. With Power clearly Major League ready but Howard needing time in the minors — the team was converting him to play catcher, the Yankees traded Power in December of 1953.

Given the amount of time, detail, planning, and consideration of off-field behavior that the Yankees required in order to put an African-American in pinstripes, I’m surprised to read that, by present-day indicators, Robinson had a checkered (albeit nearly certainly justified) off-field resume.

World War II cut Robinson’s career short — his football career, that is. Ted Williams is one of my favorite players, ever. In 1941, he hit .406 — the last player to break the .400 barrier. The next year, 1942, he won the Triple Crown. In 1946, he was second on batting average, home runs, and RBI, but lead the league in runs, on-base percentage, slugging percentage, and won his first MVP award. In 1947, he won the Triple Crown again. 1948, he lost a few games due to injury, but still finished third in MVP voting. And to top it all off, he returned healthy in 1949 to win a Triple Crown a third time, his second MVP award, and, for good measure, lead the league in doubles, too.

From 1943-1945, during the prime of his career, he served in World War II. Yet when he retired in 1960, he did so with 521 homers, then good enough for third all-time behind Babe Ruth (714) and Jimmie Foxx (534). Imagine how great Williams may have been if he hadn’t lost that time to the War. (He also missed time to a tour of duty in Korea.)

But for baseball fans, what WWII taketh, maybe it giveth back? Robinson was destined to play football — baseball was his worst sport as a UCLA student — but the war cut his football career short. And then, I learned…

Robinson ended up on the Negro League Kansas City Monarchs because of the above two things. When serving in the military, Robinson refused — in Rosa Parks’ style — to move to the back of a bus. After a few twists and turns with many refusing to take action, Robinson was brought before a military tribunal charged with two counts of insubordination. He was acquitted by an all-white panel, and soon after transferred to Camp Breckenridge, Kentucky. There, he’d meet a former Monarch player who convinced him to push for a spot on the team.

The first team to give Robinson a tryout was also the last Major League team to integrate. The Red Sox, in case you wondered.

The team was feeling pressure from local politicians to desegregate, so they brought in Robinson — but it was a dog and pony show. Even at the tryout, Robinson was the subject of racial epithets, even though the tryout was closed to the public — that is, the slurs were coming from the mouths of people in Red Sox management.

Robinson was the first African-American vice president of a major corporation. He retired from baseball in January of 1957 and joined Chock full o’Nuts, as what sounds like vice president of human resources — where he remained until 1964.

Politically, he was independent and active. Robinson endorsed Richard Nixon in 1960 — over JFK. He supported JFK afterward, and saw Kennedy as a civil rights leader. Four years later, Robinson backed Nelson Rockefeller in the primaries against eventual Republican nominee Barry Goldwater, but after LBJ prevailed in the general election, Robinson supported him more than one would think, writing to Martin Luther King Jr. in support of Johnson’s Vietnam War plan. Coming full circle, Robinson supported Democratic presidential candidate Hubert Humphrey in 1968 — versus Nixon.

I enjoy the nuanced political stance, especially given the leverage Robinson certainly had in the America of the 1960s. I also can’t help but notice that he backed the loser three times in three election cycles — but I’m not sure what that means.

***

Your turn. Read Jackie Robinson’s Wikipedia entry and leave your thoughts in the comments. And then start your own Wikipedia Reading Club meeting!

That same day, former president John Adams came up in a conversation with a friend. We were talking about Liz Cheney’s objection to American lawyers representing Al Qaeda members, and Adams — who represented British soldiers (successfully!) charged with crimes stemming from the Boston Massacre — naturally came up. We both knew who he was, basically — the second President of the United States, a Boston patriot, even cousin of Sam Adams. But beyond that? Nothing. Not even enough to fill a top 10 list.

That same day, former president John Adams came up in a conversation with a friend. We were talking about Liz Cheney’s objection to American lawyers representing Al Qaeda members, and Adams — who represented British soldiers (successfully!) charged with crimes stemming from the Boston Massacre — naturally came up. We both knew who he was, basically — the second President of the United States, a Boston patriot, even cousin of Sam Adams. But beyond that? Nothing. Not even enough to fill a top 10 list.